|

Early

Colonial American History of the Wild Turkey

In

1620, the Pilgrims disembarked from

the Mayflower onto the "New World," currently

known as Plymouth, Massachusetts. As colonist began

to search for sources of food, they met up with Northeastern

Native Americans. There new neighbors shared their

knowledge of hunting large fowl. The colonist were

surprised to see turkey cocks gobbling and strutting

on this land similar to the domesticated ones they

brought from England. The delicious meat of the wild

turkey was an important and an abundant food supply

for both Indians and settlers. Soon the New World

Pilgrims were cross breeding both stocks of Turkeys

at the Plymouth Plantation. In

1620, the Pilgrims disembarked from

the Mayflower onto the "New World," currently

known as Plymouth, Massachusetts. As colonist began

to search for sources of food, they met up with Northeastern

Native Americans. There new neighbors shared their

knowledge of hunting large fowl. The colonist were

surprised to see turkey cocks gobbling and strutting

on this land similar to the domesticated ones they

brought from England. The delicious meat of the wild

turkey was an important and an abundant food supply

for both Indians and settlers. Soon the New World

Pilgrims were cross breeding both stocks of Turkeys

at the Plymouth Plantation.

Some experts think that

roast turkey adorned the first Thanksgiving dinner

the Pilgrims had in 1621. Others credit the settlers

of Virginia's Jamestown with celebrating the first

Thanksgiving as their version of England's ancient

Harvest Home Festival.

Wild

Turkey as Our National Bird

On July 4 1776, the First Continental

Congress selected a committee to design the Great

Seal of the United States of America. It was the task

of three founding fathers: Benjamin Franklin, John

Adams, and Thomas Jefferson to select a political

icon that best reflected the new country.

Benjamin Franklin used his legendary

humor to rebut John Adams nomination of the Bald Eagle

similar to Germany's Imperial Eagle Sable. Franklin

considered the turkey, not the eagle, as a fitting

emblem for the Great Seal. To his dismay, Franklin's

turkey was outvoted by a large margin. In a letter

to his daughter he wrote:

"For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had

not been chosen the Representative of our Country.

He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not

get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perched

on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy

to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the

Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at

length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest

for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the

Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this Injustice, he is

never in good Case but like those among Men who

live by Sharping & Robbing he is generally poor

and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank Coward:

The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks

him boldly and drives him out of the District. He

is therefore by no means a proper Emblem for the

brave and honest Cincinnati of America who have

driven all the King birds from our Country....

I am on this account not displeased

that the Figure is not known as a Bald Eagle, but

looks more like a Turkey. For the Truth the Turkey

is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and

withal a true original Native of America... He is

besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird

of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier

of the British Guards who should presume to invade

his Farm Yard with a Red Coat on."

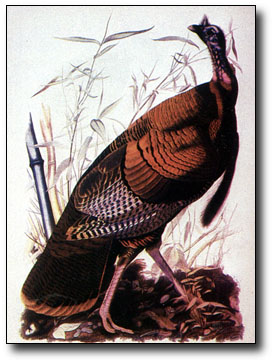

Brilliant artist and naturalist,

John James Audubon thought highly of the patriotic

qualities of the turkey.

"Male turkeys can turn their

heads red, white and blue by controlling the flow

of oxygen to their heads while strutting."

Turkeys Endangered

Although

wild turkeys could fly fast, they couldn't fly far,

so they became easy shots for hunters. Once American

pioneers discovered turkeys were not blessed with

either adequate vision or high IQs, and could be easily

trapped, they became the settler's primary source

of food. Although

wild turkeys could fly fast, they couldn't fly far,

so they became easy shots for hunters. Once American

pioneers discovered turkeys were not blessed with

either adequate vision or high IQs, and could be easily

trapped, they became the settler's primary source

of food.

The turkey trap was a simple contraption

that consisted of a covered pen with a turkey-sized

tunnel dug underneath one wall. On the ground outside,

a trail of corn led from the thicket to the tunnel

to the interior of the pen. The unsuspecting turkey

would peck up the corn, go inside the pen and become

so flustered it would be unable to find its way out.

As pioneers pushed west and cut and

cleared virgin forests, the turkey's habitat changed

and wild turkey numbers dwindled. In the late 1700s,

turkeys were harvested without restraint and marketed

for human consumption. (Some historical reports mention

that hens sold for 6 cents apiece while big gobblers

brought a quarter at game markets). Wild turkeys were

so plentiful; in fact, people looked down on turkey

as food suitable for the lower classes. Men of means,

however, encouraged turkey breeding to insure that

turkey feathers-dyed to decorate their wives' hats,

dresses and coats-remained in plentiful supply. By

the mid 1800s the Civil War brought a shortage of

food and the big bird had been eliminated from nearly

half of its original range.

In 1840 J J Audubon wrote, as to the

turkey's status in his time:

"The unsettled parts of

the States of Ohio, Kentucky, Illinois, and Indiana,

an immense extent of country to the north-west of

these districts, upon the Mississippi and Missouri,

and the vast regions drained by these rivers from

their confluence to Louisiana, including the wooded

parts of Arkansas, Tennessee, and Alabama, are the

most abundantly supplied with this magnificent bird.

It is less plentiful in Georgia and the Carolinas,

becomes still scarcer in Virginia and Pennsylvania,

and is now very rarely seen to the eastward of the

last-mentioned States. In the course of my ramble

through Long Island, the State of New York, and

the country around the Lakes, I did not meet with

a single individual, although I was informed that

some exist in those parts. At the time when I removed

to Kentucky, rather more than a fourth of a century

ago, Turkeys were so abundant that the price of

one in the market was not equal to that of a common

barn fowl now. I have seen them offered for the

sum of three pence each, the birds weighing from

ten to twelve pounds. A first-rate Turkey, weighing

from twenty-five to thirty pounds avoirdupois, was

considered well sold when it brought a quarter of

a dollar."

|